Meta's AI Chatbots in a Global Community

How Meta's vision for human "connection" slipped away

What does it mean to have a meaningful “connection?” Why do we feel compelled to “share” within a digital “community?'

Meta has been trying to define terms like “sharing,” or “connection” for us arguably since its inception, resorting to an evolving set of definitions over time. We once “connected” face-to-face, through letters or over the phone, then came online messaging, then “posting” and “liking,” then sharing and commenting on digital posts. This was how we “connect” and “share” into the 21st century.

On December 27th, we learned about the next phase of online engagement from Meta’s Connor Hayes, vice president of product for generative AI at Meta:

[Meta] is rolling out a range of AI products, including one that helps users create AI characters on Instagram and Facebook, as it battles with rival tech groups to attract and retain a younger audience. “We expect these AI’s to actually, over time, exist on our platforms, kind of in the same way that accounts do,” said Connor Hayes, vice-president of product for generative AI at Meta. “They’ll have bios and profile pictures and be able to generate and share content powered by AI on the platform… that’s where we see all of this going,” he added.

This is where “we see this going,” says Hayes, but do you?

Apparently not. The AI accounts were rolled out a week ago and then quickly deleted by Meta due to user’s interactions with the “AI-slop” being generated by these AI accounts. People replied to the chatbot’s posts with anger and frustration, especially about their inability to block the accounts or the AI’s strange approach to navigating questions about representation.

This should come as no surprise: Meta has always been in the “move fast and break things” business, attempting to read the tea leaves when it comes to user experience even before the tea is made. The directory-based, earlier version of Facebook was quickly scrapped for a larger, “social infrastructure” platform for connecting that included a chronological newsfeed, which was quickly scrapped to become an algorithmically-driven newsfeed based on likes and sharing by people and organizations run by people, which is now quickly scrapped to become a platform designed to connect not just people and organizations through algorithms, but AI chatbots as well. Do people want this? I’m not sure, and this is all a guess as to “where things are going” into the future. However, Facebook has consistently offered a corporate vision of the future that aligns with its company’s agenda.

Such future-making can become “a strategic resource” for a corporation looking to proactively attract new customers to its platforms.

Meta’s effective, rhetorical tactics help massage these digital adjustments into a comfortable reality for users on its platforms, whether they are wanted or not. For example, communication scholars have noticed that Zuckerberg’s rhetoric regarding user control “give users the appearance of more control by simplifying and expanding the tools to manage the ever-increasing volume of friends’ messages, links, photos and videos online,” which helps “reconceptualize privacy within a rhetoric of control” while obfuscating the datafication of users. Other scholars have argued Zuckerberg’s specific use of the term “sharing” works to depoliticize a complicated field of social and capital relations on its platforms, effectively helping to monitor and commodify users.

But it’s this notion of human connection and a global human community that has been the focal point of Meta’s marketing campaign for over a decade. The central problem our planet was facing, according to the implied understanding of Meta’s corporate messaging, was a lack of global connectivity. This was an important pattern observed in a recent analysis from Joachim Haupt, who reviewed the Zuckerburg Files and noticed that Zuckerburg consistently framed global challenges as problems centered around a lack of connectivity. Some snippets from Haupt’s article, quoting Zuckerburg files:

In an early statement, for example, he [Zuckerburg] states that terrorism “comes from just a lack of connectedness and a lack of communication, a lack of empathy and understanding” (2008-16).

and

Zuckerberg’s causal assumption has an obvious consequence: “Connecting everyone is one of the fundamental challenges of our generation” (2014-151).

and

Zuckerberg argues that connectivity contributes to prosperity and growth, and the economic division of society could be reduced “by getting everyone online, and into the knowledge economy—by building out the global Internet” (2013-101).

and also

“People sharing more—even if just with their close friends or families—creates a more open culture and leads to a better understanding of the lives and perspectives of others” (2012-48).

For Meta, human connection solved problems. After its IPO in 2012, Meta’s messaging often argued that better connectivity meant more connectivity. More “access to opinions” and more “openness” on the platforms was an improvement. However, this quantitative approach to connecting quickly gave way to a qualitative approach, where Zuckerburg consistently argued for the value of a “global community” that isn’t just about the amount of connections, but the quality of connections. As seen in quotes in the Zuckerburg Files, In 2016 and 2017 we heard more about “meaningful communities,” “meaningful social interactions,” “richer tools” and discussions of “a world where everyone has a sense of purpose.” This “social infrastructure for community” became something larger than just a space for any type of connection, but a utopian Global Village that exists “for supporting us, for keeping us safe, for informing us, for civic engagement, and for inclusion of all.”

Us, as in people, right?

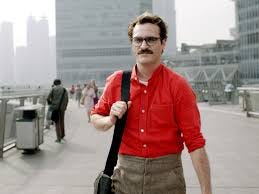

Global connectivity has been the centerpiece of Meta’s messaging, suggesting that quality connections lead to something larger for its human users. When you add AI-slop to the equation, that narrative is disrupted pretty aggressively. I’m not sure users can just memory-hole that consistent corporate message and quickly slide into a world where the default user on Meta’s platforms is Joaquin Phoenix in the movie, Her.

Maybe the tech isn’t ready just yet. Maybe there is a seed of demand for AI accounts, especially among younger generations waiting for their AI buddies to flood Meta’s platforms. Meta probably thinks so, suggesting that this recent glitch was due to “confusion” about their “vision:”

“There is confusion,” Meta spokesperson Liz Sweeney told CNN in an email. “The recent Financial Times article was about our vision for AI characters existing on our platforms over time, not announcing any new product.”

Ah, yes, the “vision” was misconstrued. Given Meta’s history of creating that vision for its users, I’m sure this mistake in how we see our future will quickly be fixed.