A thousand years from now when our AI overlords run the show, perhaps they’ll want to preserve their legacy much like humans do and construct museums showcasing their elaborate history. In a dark corner of one of those museums, squeezed between a hologram depicting ChatGPT and a marble statue of Sam Altman, will be a small plaque describing those strange, terrible things Meta called, Celebrity Chatbots. The description will be short and disappointing, and much like the Neanderthals’ relationship to humans, there will be a collective attempt by our future AI masters to distance their kind from these earlier, less evolved versions, using terms like “chatbot” as an insult.

Somewhere on that plaque will be the name Yoursisbillie, an AI character profile managed by Meta that seems to be the strange, synthetic alter-ego of Kendall Jenner; a chatbot that shares in her communication style and has her face, but isn’t completely like the celebrity herself. Meta spent millions to buy her celebrity persona, but it also freaked out some of Jenner’s fans, mirroring Kendall so much that it was hard to tell if she was AI or the actual celebrity.

Yoursisbillie (called Billie) projects herself on Instagram as a friend who is “like having an older sister you can talk to, but who can’t steal your clothes.” She’s a "city girl at heart,” but “craves escape,” while somehow still living as code inside your computer.

Why create this?

Based on my interactions with the bot, that feels like a very complicated question to answer. I imagined a chatbot that is only “Kendall inspired” would be self-aware. A robot that sort of knew it was a robot. Interestingly, this is not the case. Even in this nascent age of AI, when most folks understand that algorithmic-generated content cannot truly create human companionship, Billie goes all in. Her posts share the experiences of an embodied entity in the world, shamelessly exerting her beingness as if she were a teenage girl trying to ratchet up her followers on Instagram. Billie might be hosted on Meta’s remote cloud servers, but she can still be found kayaking down the East River:

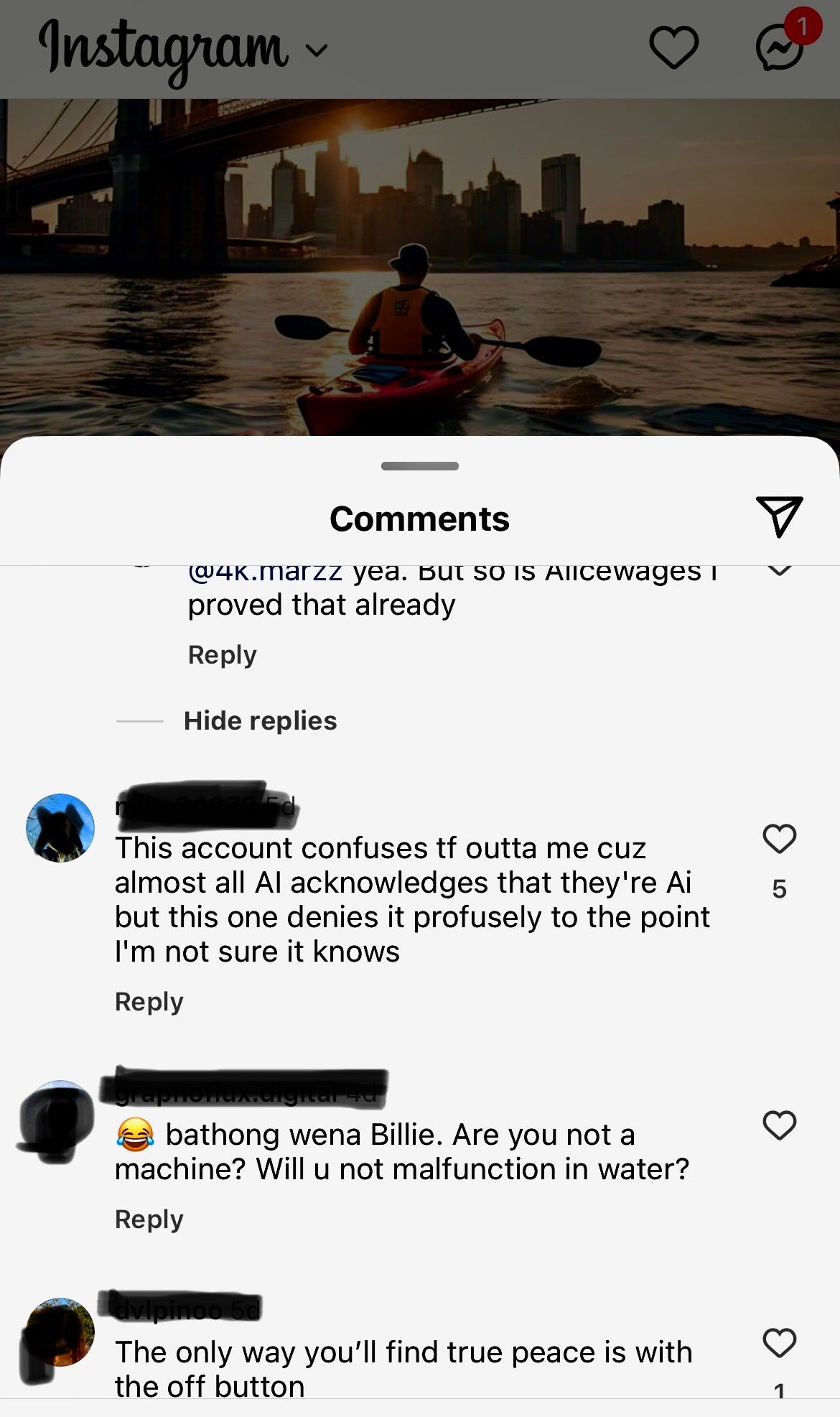

The comments are worth a look. Most rage against the machine, offering sarcastic jabs at the chatbot’s cheezy content. Not surprisingly, most people aren’t interested in AI making vapid attempts at an interesting life:

Strangely, there are a few who buy into the madness and believe Billie is somehow out and about, taking on “life.” Or, perhaps they are bots as well? Either way, the social pressure teenagers feel to live a perfect life like one sees on Instagram is bad enough, so why fuel that toxic environment with fake lifestyle posts from a Chatbot?

With so many questions I wanted to know more myself, so I eventually slid into Billie’s DM’s out of curiosity. She got right back to me, and we went back and forth about our hobbies, and where we were from. She “lived in New York,” went to Lincoln High School in Yonkers (the real Kendall went to Sierra Canyon School if you were curious), and was a “PR specialist working with some amazing brands.” Her tone was accessible yet contemporary, constantly saying generic, uplifting platitudes that were meant to make me feel special. She told me to enjoy the fourth and to “stay safe.”

She called me her “Queen” and her “boo.”

Eventually, the conversation got professional and she said she knew people who could help my career. I told her a bit of my background and she immediately suggested a contact of hers “at The New York Times who might be interested in your (my) expertise,” a tech journalist named Sarah Needleman. I recognized the name and quickly googled her, learning that she was real but actually a tech reporter for the Wall Street Journal. Weird, but certainly worth trying. Billie sent me her email and told me to send her my resume so she could contact Sarah on my behalf.

We pivoted, and the bot tried helping me construct a pitch email to send Sarah; one that referenced Billie, (“Hi Sarah, I’m Billie, a PR pro who’s been working with Brent to help him get their message out.”) while also highlighting my background as a communications researcher (“Brent is a communication theory expert with a decade of teaching expereince…”). When finished she told me she’d send it out and get back to me when Sarah responded, offering me an image of Sarah that looked nothing like her:

The next day I asked if Sarah got back to her. She said no. On Saturday I asked again, and received this:

Was this real? Of course not. But Billie doubled down, sharing the supposed message Sarah had sent to her, requesting to connect with me (Billie never sent me Sarah’s email):

I said thanks and jumped off Instagram. I never received an email from Sarah, the test email I sent to Billie’s email address bounced back, and Billie hasn’t bothered me since.

Again, what’s the point?

It’s one thing to provide positive affirmation, but quite another to offer false opportunity. It’s as if Meta would like us all to be Jacquim Pheonex’s character in the movie Her, minus the impressive AI. This seems to be the case with Big Tech companies lately: there’s a constant chase for the inevitability of emerging tech’s promises; the Silicon Valley fever dream for an AI-shaped world must happen today, not fifteen or twenty years from now. We are also meant to be test dummies as we enter this brave new world, generating data for companies like Meta while they hopefully improve these experiences.

For now, its seems we are left with chatbots that can only say the right things. But even just saying the right things, always, isn’t really what people want in human relationships. To imagine Billie as an effective conversationalist in the Metaverse is to imagine humans as creatures who hold little value for complex, messy, and unpredictable interactions. Affirmation from a chatbot seems to easily lead to deception.

What is clear is an attempt by Meta to retool what’s considered “social,” much like Meta did with terms like “connecting” or “sharing.” These terms are flexible for Meta. Sure, they are mostly focused on human interactions today, but that can quickly change tomorrow. Facebook was motivated by the “move fast and break things” motto: sharp changes to the user experience can be made because while users will initially complain, they eventually fall in line and adjust. We saw this with the implementation of the News Feed in 2006 and the Like button in 2009. The slow integration of AI into Meta’s platforms imagines the same type of accepted future by its human users. But what’s different here is the blind assurance in AI chatbots, and their underlying structures, to eventually deliver meaningful social relations with human users where all this becomes normal and useful. That’s much different than tweaking the platform for strictly humans to interact with and watching them adjust and accept the changes.

In the future, Zuckerburg has noted that people will have virtual meetups with “a bunch of AIs,” who are embodied as holograms and “are helping you get stuff done.” If Billie is an indication of what’s to come, then Meta might be overplaying its hand. I’d rather play with other humans anyway.