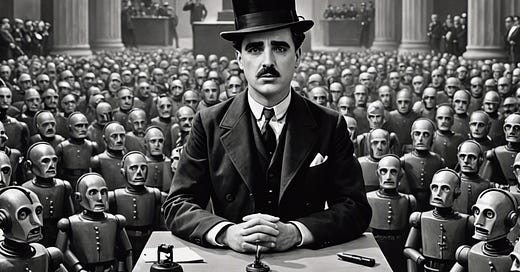

You are not machines! You are not cattle! You are men!

Chaplin’s rousing speech in his film, The Great Dictator, highlighted the symbiotic relationship between two human desires: technological progress and rationalization. We love our new machines, and our ability to make sense of the world, but might these two human drives harden our sensibilities? Might we notice that “more than machinery, we need humanity?”

We are not “cattle” or “machine men” as Chaplin argued. Today we are simply “users” in our digital worlds, a term regularly deployed to describe any person engaging with technology, be it engineers, corporate bosses, chatbots, or video game athletes. “Users” can accurately describe someone using software, to be sure. However, it is also broad enough to describe almost anything and say nothing. The “user,” according to tech writer, Taylor Majewski, can be “applied to almost any big idea or long-term vision:”

Though “user” seems to describe a relationship that is deeply transactional, many of the technological relationships in which a person would be considered a user are actually quite personal. That being the case, is “user” still relevant?

When we are labeled as “users,’ the notion of collaboration with the digital tool slips away, and we are only acting on the technology, rather than seeing a more reciprocal relationship between human and machine. By focusing only on technological utility, we fail to see the deeper implications of how technology mediates our interactions in the world and becomes a co-agent in this construction of what defines us as “human.”

These arguments are central to the theory of Posthumanism. Posthumanists have argued that human practices are one component of a complex assemblage of interactions among both human and nonhuman entities in which separation of subject and object becomes impossible.

In other words: you are not your phone, but you are certainly a different type of person because of your interactions with your phone.

When we slowly flatten our relationship with technology to a “user,” much of the impact technologies have on us becomes unseen. This is what social psychologist, Johnathan Heigt, has been revealing to us on his recent book tour. He blames the spike in teenage depression on the rise of smartphones and social media during the mid-oughts. The perfect storm of Twitter, Instagram, smartphone notifications, and front-facing cameras that emerged ten years ago has made teenagers easily distracted and rushing towards instant entertainment on their phones rather than coping with their emotional lives. “The iPhone isn’t just a tool,” he argues, “but a tool of mass distraction.”

No one is saying to disregard one’s phone completely. But we might consider how our language provides a particular smokescreen to our interactions with emerging technologies. The term “user,” for example, is not only ubiquitous but flexible; it predetermines a relationship with an object that has been proven to be much more complex than previously thought. Most conveniently, it fits nicely in the array of futures certain corporations want to present to us. As Majewski argues:

The ubiquity of “user” folded neatly into tech’s well-documented era of growth at all costs. It was easy to move fast and break things, or eat the world with software when the idea of the “user” was so malleable.

Other terms have had the same effect in Big Tech’s rhetoric. The terms “sharing” and “connecting” are constant in Mark Zuckburg’s speeches, effectively creating a more modern, post-digital understanding of how one builds relations in and outside our virtual worlds. But communication scholars have noticed how terms like “sharing” depoliticize social and capital relations within the platform, mask Meta’s commercial interests, or support legal rulings concerning privacy and users’ acceptance toward monetization.

As AI grows in popularity, one notices language that presents AI chatbots as neutral tools for utility as well. We have “co-pilots,” and AI “assistants,” terms that suggest objects in waiting, ready to be acted upon.

But tech can react and integrate with us in unpredictable ways. A recent study some colleagues and I completed on XR marketing and user experience concluded that users were not simply enhancing their abilities through this new technology, but at times feeling dizzy, becoming creative, or feeling at peace while using virtual reality. These reactions were much different than experiencing an enhanced or expansive virtual space, which was exactly what the marketing language suggested.

In the end, we are more than users of technology. We are doing something else than just “connecting,” or “sharing” on our social media platforms. Perhaps we are rushing to these terms to highlight our desire to be productive, rational beings. Surely, this can be a good thing. But maybe our “knowledge has made us cynical” at times, as Chaplin put it, and might “we think too much and feel too little.”

Good read Brent!