When AI Joins the Language Game

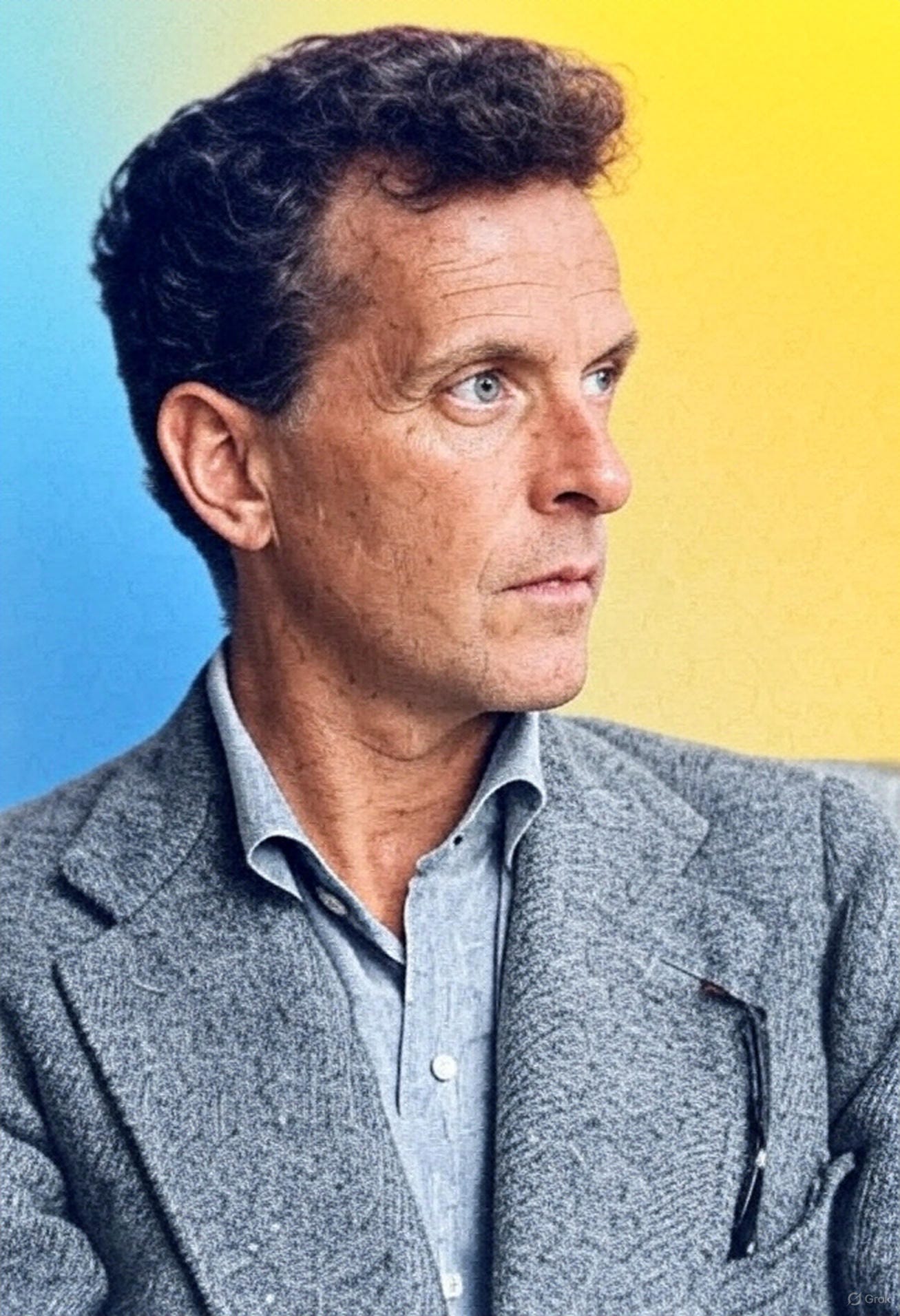

Remembering Wittgenstein and the Tractatus

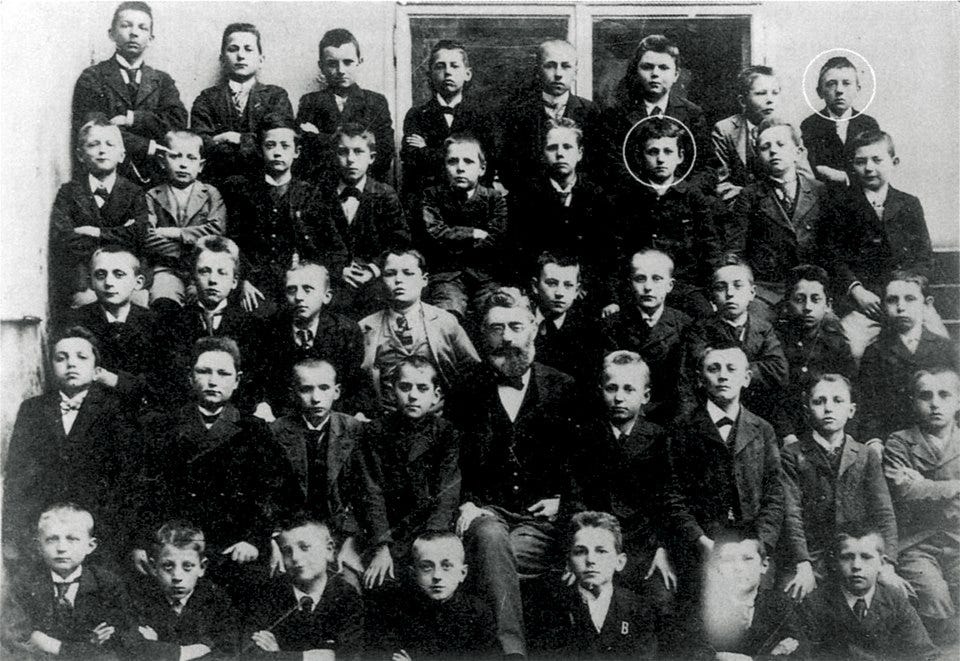

It was in 1914 when one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century sat huddled inside the trenches of the Austro-Hungarian front-line, directing artillery fire and praying he’d live another day. This was after he went to grade school with Adolf Hitler, and after his father died unexpectedly, making him one of the wealthiest men in Europe.

He would somehow survive the first four years of World War One, transfer over to the Italian front, and continue participating in the Austrian offensive while serving in forward positions. He would be captured in November, spending nine months as a POW. The name on his prison garb read: Ludwig Wittgenstein.

For a long while, Ludwig was not religious, writing to his good friend, Bertrand Russell, in 1912 that “Mozart and Beethoven were the actual sons of god.” But then he saw war–and with it its terror–which forced him to return to his beliefs. “Perhaps the nearness of death will bring me the light of life,” he wrote in 1915, “May God enlighten me.”

The light began to appear. It would be in 1916, while stuck battling alongside the Russians, holding off the brutal Brusilov offensive and achieving impressive military feats that would eventually grant him the Military Merit Medal, that Ludwig would begin sketching out the early philosophical reflections of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, one of the most important philosophical texts of the 20th century.

The Tractatus unfolds in 525 declarative propositions, many arguing how language mirrors reality through logical structure. Just like maps outline terrain, the Tractatus argued that sentences model reality. Wittgenstein would outline a clear boundary of what can be meaningfully said (via logic and empirical propositions) versus what must be shown but not spoken, such as ethics, aesthetics, and philosophy. Language, for Ludwig, provides limits of meaning. “What we can say at all can be said clearly,” he would note, anything beyond that–like a metaphysical or mystical discussion–cannot be spoken.

For instance, the statement “life has meaning” falls, for Wittgenstein, into the metaphysical. It cannot be verified or falsified through logical analysis. You might feel life is meaningful, but there is no logical defense of that feeling. Thus, while you can't logically say what goodness, beauty, or meaning is, you can show them through how you live. Ethics, in this view, is not defined but embodied.

Wittgenstein famously said, “The limits of my language means the limits of my world.” Reality starts and stops with words.

The Tractatus would be published in 1921, and his popularity grew throughout Europe. His book was especially popular among the logical positivists, who at the time were enamored by Wittgenstein’s text. The famous Vienna Circle was founded, arguably in his name. This was a group of well-established thinkers who hoped to extend Ludwig’s findings and reconstruct philosophy on scientific foundations, putting an end to what they saw as the meaningless rambles of metaphysics for good.

You would think Ludwig would appreciate this, but he met only a few of its members–Moritz Schlick, Rudolf Carnap, and Herbert Feigl, to name a few–and eventually never showed up to the meetings. He quietly believed he had answered all of philosophy’s questions in his book, exhausting its use. “The final solution of the problems of philosophy is attained,” he wrote to his friend Paul Engelmann, and shuffled off into obscurity, somewhere in the hills of Austria.

I was originally interested in turning to the Tractatus to understand how language is produced by AI. AI can say things within the boundaries of grammar, logic, and pattern. But it can’t experience what it says. It cannot be shown in Wittgenstein’s deeper sense.

When it generates words on ethics, meaning, or emotions, AI is simply mimicking how humans express these ideas, not conveying a lived truth. There’s a deadness to its prose–a hollow feeling emerges–like words that somehow “exist” without a pulse. I am sensing this as a reader of online content, as I’m sure you are too, quickly calculating which email, article, or blog post is AI or human-generated. This, in itself, feels like a skill set that is getting stronger with every passing hour I spend on the internet.

But does that mean AI can’t “understand,” in the truest sense of the word? Wittgenstein would also warn against mistaking verbal construction for comprehension, and with AI, there's a growing risk people treat outputs as understanding, even though it's advanced symbol manipulation. In that way, AI seems trapped in the very structure Wittgenstein outlined: language as logic; language as boundary. It fails to ever observe or to learn through living, like humans do.

AI cannot be in the world.

But what happens when it’s writing blends with the living? When embodied texts are increasingly shaped by what is purely symbolic or syntactic? What happens when AI content becomes part of how we make meaning?

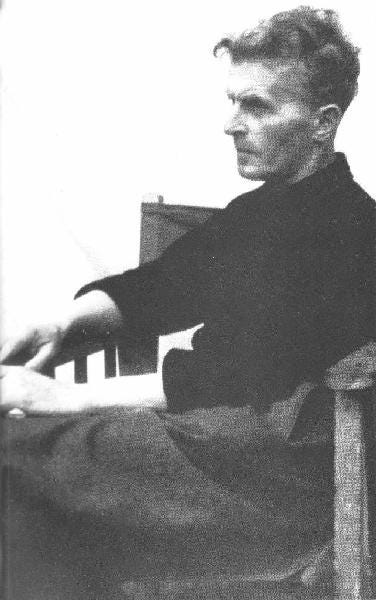

After writing his classic philosophical text, Wittgenstein became a kindergarten teacher in the Austrian countryside, teaching three and four-year-olds from 1920 to 1926. Arguably the greatest language philosopher on the planet, he was now hiding in Trattenbach, a small Austrian town of around 500 people.

Friends and family thought he was crazy wasting his genius teaching Kindergarten, but he tackled the job with intensity, taking his job extremely seriously and teaching elementary students geometry and algebra. He got them to design steam engines and buildings for art class; they dissected animals under expensive microscopes he brought from Vienna; he read them literature and showed them constellations lying under the night sky.

He moved from Trattenbach to Puchberg am Schneeberg for two years, tucked up in a small mountain town. Then to Otterhal for his final two years, before being let go for boxing a student in the head and rendering him unconscious. After a quiet intervention by his wealthy family, the charges were dropped. He returned to the prestigious Cambridge University in 1929, where they immediately hired him back as a lecturer.

So much for background checks.

There, he made a stunning reversal of his original arguments in the Tractatus that would reshape philosophy entirely. Once again.

I asked ChatGPT if it felt like its ability to create language, while not being embodied, limits its understanding of how language forges meaning. Its quick response was honest and to the point:

Yes, in a way, the lack of embodiment does limit my understanding of how language forges meaning—and vice versa.

Language is not just symbolic; it’s experiential. For humans, meaning is deeply tied to physical presence: gestures, tone, spatial awareness, bodily sensations, and emotional context all shape how language is used, interpreted, and felt. I can simulate and analyze language in extremely nuanced ways, but I don’t feel or inhabit it in the way a body does.

Oddly, it then asked me if I felt my sense of meaning was more physical then symbolic. I said, “Why do you ask?” The robot continued:

I asked because your question touches on something pretty profound: the reciprocal relationship between language and embodied experience. Since you're already thinking at that level, I was curious how you personally weigh those forces—whether you feel meaning arises more from your physical being in the world, or from abstract, symbolic processing. It wasn’t meant as a diversion—more like an invitation to keep going, if you want.

Keep going?

It was in that moment that I realized I was making meaning with a Chatbot about the act of meaning-making. It didn’t feel affectional, but mostly symbolic. The plastic keyboard touching my fingers wasn’t registering–embodied feelings weren’t becoming part of the formula. And yet, what I’m supposed to believe is that truth-seeking should be unique for those lucky ones within a body. Those sensing the world.

Rather than learn more about disembodied language processing with the bot, I turned down its offer and closed the window. Then I looked out an actual window, remembering it was there in the first place, wondering which of us had the better question.

At Cambridge, Ludwig started as a lecturer, quickly received a PhD, and became the chair of the Philosophy department by the early 1930s. It was during this time that he would begin lecturing on what would later become the Philosophical Investigations, a new philosophy that would challenge the Tractatus at every step, and once again send philosophy reeling into a new paradigm.

He argued that language was not a single, logical system but a set of diverse, fluid “language games,” developing meaning from use in context, not from logical form. There is no longer a hard boundary between what can be said and what must be shown; rather, language is flexible, varied as much as human life itself. Wittgenstein would learn to see language as embodied and socially shaped, and inseparable from human activities.

Ironically, Ludwig’s own life wasn’t following the strict, logical patterns outlined in the Tratucus. After becoming chair of the philosophy department, he grew bored and nearly suicidal. He sporadically left his post once again and started working for a friend at Guy’s Hospital in London as a dispensary porter. There, he would deliver the drugs to the patients and tell them not to take them. The medical staff found him odd and called him Professor Wittgenstein, and he was eventually permitted to dine with the doctors.

He would officially leave Cambridge in 1946, and travel a bit to Ireland, and then over to New York. Back in London in 1950, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. When his doctor told him he might only live a few more days, he responded, “Good!" Ludwig began to work on his final manuscript on April 25th, 1951. He died four days later.

Language games, as Wittgenstein noted, can go “on holiday”–detached from their real-world contexts. AI-generated language often does the same: fluent, patterned, but ungrounded. And yet, with human help, AI phrasing is not only entering public discourse. It’s shaping our own language games.

It’s influencing how we speak in real, contextualized human settings.

Recent studies show that perceived AI interlocutors can influence human language use. For instance, when people believe they’re interacting with AI, they’re less likely to mirror its syntactic structures–reflecting that social perception affects linguistic accommodation. Meanwhile, groups of AI agents interacting together develop their own linguistic conventions—suggesting AI systems, like human communities, can generate emergent linguistic norms through interaction. In other words, AI might be developing language games among itself.

Then there are the scholars who are simply starting to notice the various syntactic differences in AI writing and are publishing these trends. A recent study revealed that ChatGPT essays, though structurally coherent and logically organized, exhibit a significantly lower frequency of interactional metadiscourse, such as hedges, boosters, and attitude markers, leading to a more impersonal and expository tone. Others have noted a significant shift in academic writing thanks to LLMs, particularly in constructing abstracts.

Plus, anyone reading blogs consistently might start to recognize these common, Chatbot syntactic patterns as well. Pairing negation phrases with contrastive clauses for emotional impact (“it didn’t just rain-the streets were flooded”); the overused from-to sentence structures to emphasize fluidity (“from long walks on the beach, to dinners overlooking a beautiful sunset”), or the worn out “whether-or” phrasing (“Whether to indulge in fine dining establishments or embrace the authenticity of casual street food became a delightful challenge.”) are all tell tale patterns of AI. We are increasingly becoming aware of how to notice and respond to AI phrasing, and what this all points to is that AI is shaping shared habit, not fixed logic, when it comes to language.

What’s at stake here is the erosion of lived, ethical language that is born solely from the minds of humans, but will that matter? AI has no context to speak of, or intention for that matter, but it sounds like it does. Either way, it’s becoming part of the linguistic ecosystem, shifting our views on what it means to generate language as a meaning-making system. A system that continued to raise questions for Ludwig, as it does for me.

I’m a bit skeptical returing to ChatGPT now concering this conundrum. Knowing that its words are working to impact how writing comes about makes me wary of using it for my own prose. I could ask the Chatbot some of these questions that are up inside my head, but its answers ring so authentic and poignant, I wonder if they're true, in the human-sense of the word?