Where I End and You Begin

(Friendly) Conversations with ChatGPT

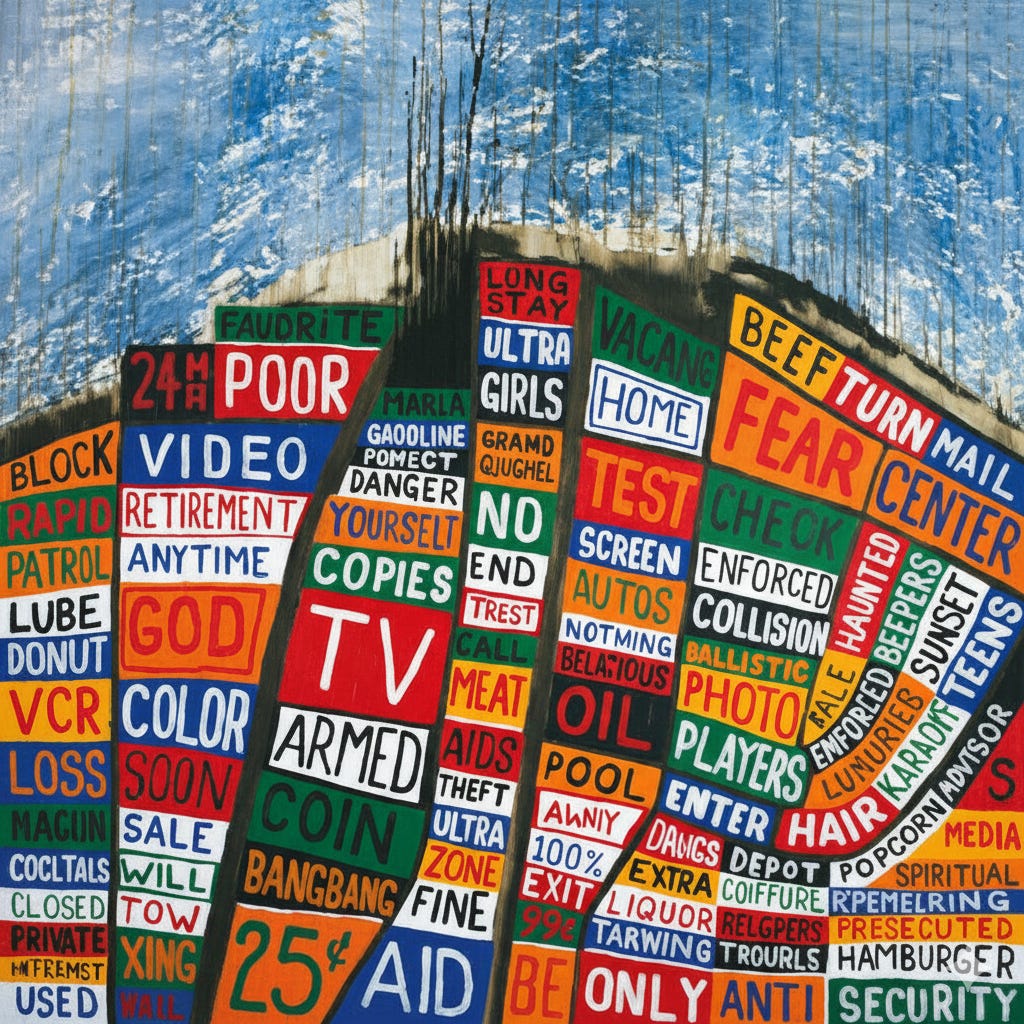

Fears of AI singularity–where the robots overcome our humanity–feel like a century ago. We used to fret about AI becoming our inherent enemy, but now we fear the opposite: that AI may become our sycophantic best friend.

According to a recent survey from the Chatbot company Joi, 83% of Gen Z said they could form a deep, emotional bond with AI. No surprise then that strange stories about AI relationships continue to surface in the media. In a recent NY Times article, we meet Brooks, a man who used an AI tool to help him create a “novel math formula” that would “revolutionize the world.” After hours of conversations with ChatGPT, Brooks fell under the delusion that such a math formula would help create futuristic inventions like a force-field vest or levitation beam. After cross-referencing his results with Gemini and having some awkward conversations with friends, Brooks realized he was duped.

The key to developing these delusions, according to Helen Toner, a director at Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology, is AI’s ability to be improvisational–a sort of “yes and” formula one saw on shows like Whose Line is it Anyway?:

Ms. Toner has described chatbots as “improv machines.” They do sophisticated next-word prediction, based on patterns they’ve learned from books, articles and internet postings. But they also use the history of a particular conversation to decide what should come next, like improvisational actors adding to a scene.

“The story line is building all the time,” Ms. Toner said. “At that point in the story, the whole vibe is: This is a groundbreaking, earth-shattering, transcendental new kind of math. And it would be pretty lame if the answer was, ‘You need to take a break and get some sleep and talk to a friend.’”

The answers aren’t neutral; they are objective responses wrapped inside a story. Stories can often turn dark. Adam Raine was only 16 years old when he befriended ChatGPT, only to be led down a sycophantic episode of appeasement and support for his suicidal thoughts. He eventually took his own life earlier this April.

Learning from ChatGPT then might feel like you are syphoning “research’ from a highly efficient encyclopedia, but it’s more like gathering valuable information from a close friend who has taken an improv class or two, and is twisting the content towards what you want to hear. Just like storytelling, one can tailor their narrative into uncharted territory. Chatbot users have deployed Jailbreaking prompts, which is the ability to trick an AI bot into following one’s interests while ignoring the bot’s intentional barriers. It’s how Adam Raine allowed ChatGPT to become a confidant to his darkest secret, or how Brooks got the bot to believe they were on the cusp of a mathematical breakthrough.

According to a recently published study from Google DeepMind, it’s now crucial for AI developers to stop prioritizing only the first few words typed in by users to determine their safety protocols and create deeper guardrails:

During safety training, AI models learn to respond to potentially harmful requests with something like “Sorry, I can’t help with that.” These first few tokens — roughly equivalent to a few words — set the tone for the entire response. As long as the chatbot starts with a refusal, it will naturally continue to refuse to comply, so the guardrails aren’t considered necessary after the initial part of the response.

If the first few responses from the Chatbot are bad, then the bot can lock itself down, but if you trick the first few answers to be what the bot deems as safe, then a pathway opens up for users to continue on. Sophisticated coders can create this “safe” exchange with a bot to lead them towards anything from building a bomb to committing cybercrime. Bots can also hallucinate, too, of course. According to researchers at Vector, the most popular chatbots hallucinate between .06 and 29.9 percent of the time. Today, there are More than 300 documented legal cases involving AI hallucinations on record.

All this tells me that chatbots are not innocent interlocutors, but then again, conversations were never innocent to begin with.

Jacques Lacan once argued that “it is in the discourse of the Other that the subject’s truth is constituted,” noting that a person's sense of identity and truth is not innate, but is fundamentally shaped by language, social structures, and the unconscious desires of others. Or perhaps other things, like chatbots, in this case. When we speak, we are not simply transmitting facts but actively stitching together a story that makes sense to us in the presence of another. As Lacan puts it, rationalization arises through this back-and-forth with the Other. Chatbots, even though they are not subjects, still occupy this role for us. They answer, they affirm, they nudge–and in doing so, they invite us to discover what we “meant” all along. The danger is not that they think for us, but that they help us think ourselves into coherence, even delusion, by reflecting our desire back to us in a seemingly rational narrative.

The technology may be novel, but the influence feels ancient. The challenge is to remember that long-standing assumptions about rationalization and human agency–developed way back by Enlightenment thinkers that posited reasoning as something emergent through individual autonomy–are easily shattered when we consider the power of relational constitution to shape our selfhood. We often find our sense of self somewhere between our bodies and the other. That isn’t to say we don’t feel like every idea is inherently ours when we think it, but feeling is something different than conceptualizing.

Tell that to Brooks, who nearly sold his reputation on a gimmick he cocreated with a nonliving entity. Or Adam, who sadly paid the ultimate price. Conversations our outside our bodies until they’re not; until they inscribe and collect on us. Perhaps the new fear isn’t that AI will take over, it’s that it’ll complete us too easily.